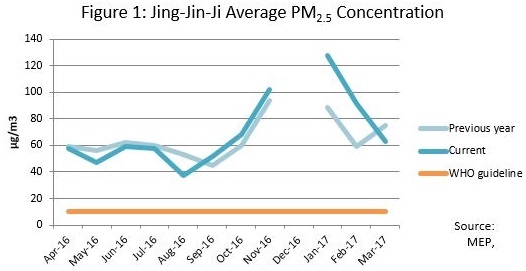

Despite the Chinese government’s extensive efforts to improve air quality per the State Council’s “Ten Measures” Action Plan and implementation of regional air quality control measures, air pollution recently worsened in the Jing-Jin-Ji region (Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei). After months of consecutive improvement last year, air quality progress slowed and then stopped in the fall of last year. For the first two months of 2017, air quality in the Jing-Jin-Ji region severely declined, with PM2.5 concentrations increasing by 48 percent year-on-year to levels more than ten times the World Health Organization (WHO) standard and well above the 60 μg/m3 goal that Beijing is supposed to achieve by the end of 2017 (see Figure 1, based on available data from the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP)).

Some experts, including the MEP, have attributed declining air quality to increased industrial production, particularly steel, cement, and coke. However, measuring air quality is a complex issue with many variables, so it is difficult to draw precise conclusions about the activities that caused recent air pollution—and about how these activities interact—based on the available data.

We know that industrial activity produces pollution. But global best practices and experiences offer tools for mitigating the effects of industrial production on air quality. Improving the efficiency of steel production and expanding the successful energy and coal savings programs completed under the “Top 10,000” program will save energy while reducing air pollution.

Energy Efficiency: A Proven Air Quality Improvement Measure

The Top 1,000 and Top 10,000 programs completed during the 11th and 12th Five-Year Plans saved significant amounts of energy and coal, and reduced emissions of key pollutants. For example, industrial boiler upgrades avoided an average of 170 tons of NOX and 410 tons of SO2 per facility every year, while industrial system optimization avoided an average of 150 tons of NOX and 350 tons of SO2. Air quality models can evaluate the degree to which emissions are reduced by energy efficiency measures. Modelling results will allow air quality officials to sort control measures by their efficacy to reduce pollution, and can prioritize which measures to tackle first. Officials can also include these measures in the air quality management plans they are completing and implementing across over 300 Chinese provinces, cities, and counties.

Use Air Quality Plans to Prioritize Energy Efficiency

Despite high-level policies prescribing the use of energy efficiency as an air quality strategy, local air quality plans often lack specific efficiency measures. Institutional barriers prevent air quality and energy officials from working together and sharing information. To help officials overcome these barriers, the Clean Air Alliance of China has created a series of templates, which contain a stepwise process for including industrial energy efficiency projects in air quality management plans and permits.

Link Permits to Energy Efficiency Performance

Another way to address the absence of energy efficiency measures in air quality plan would be to build on the success of the Top 1,000 and Top 10,000 programs and use China’s new permitting system to create a mechanism for linking energy efficiency to air quality. The key elements of the Top 10,000 program for coal and energy savings can be included as specific terms and conditions in operating permits. The permitting system can also require facilities to complete energy efficiency audits as a condition for receiving a construction or operating permit. Audits identify energy savings projects that can be completed on-site, and a permit will require all cost-effective energy savings projects to be completed as part of the criteria to receive a permit. Once the permit is issued, periodic energy audits, say every five years, can be carried out to further improve energy efficiency.

The EU Industrial Emissions Directive offers inspiration. Its holistic approach stipulates that all industrial activity be evaluated on a plant-wide basis. This avoids potential unintended effects, such as an energy efficiency measure that inefficiently increases water usage. While using this integrated approach, the definition of Best Available Techniques (BAT) accommodates industry- and site-specific practices. As compared to the prescriptive American practice that focuses only on air quality and requires the “best” technologies to be installed on each and every emission point, the EU system requires the facility to install BAT for all media: air, water, and waste. A similar, facility-wide approach is useful in China, as industrial practices changes rapidly, and water and land pollution remain significant environmental concerns.

Increase Steel Recycling

More efficient steel production will particularly benefit Jing-Jin-Ji and other areas in the proximity of steel production. Increasing recycling rates improves efficiency, as recycling steel requires only one-third of the energy used to produce steel from iron ore, and also emits much fewer air and water pollutants.

During the 13th five-year-plan period, China aims to double the share of steel produced from scrap compared to the 12th five-year-plan period, while reducing absolute steel output. However, the Chinese steel industry will still need to drastically increase recycling rates to fully utilize the estimated quantities of available scrap. As has been done in several EU countries, officials can encourage steel recycling by promoting sorting, banning landfilling of recyclable materials, or making landfilling the most costly option.

Conclusion

China’s Top 1,000 and Top 10,000 programs demonstrably reduced emissions of key pollutants. Building on these programs to accelerate energy efficiency practices and incorporating efficiency measures into air quality plans will help to ensure that industrial activities also contribute to improved air quality.

A version of this post originally appeared in chinadialogue. This post is also available in Chinese here.