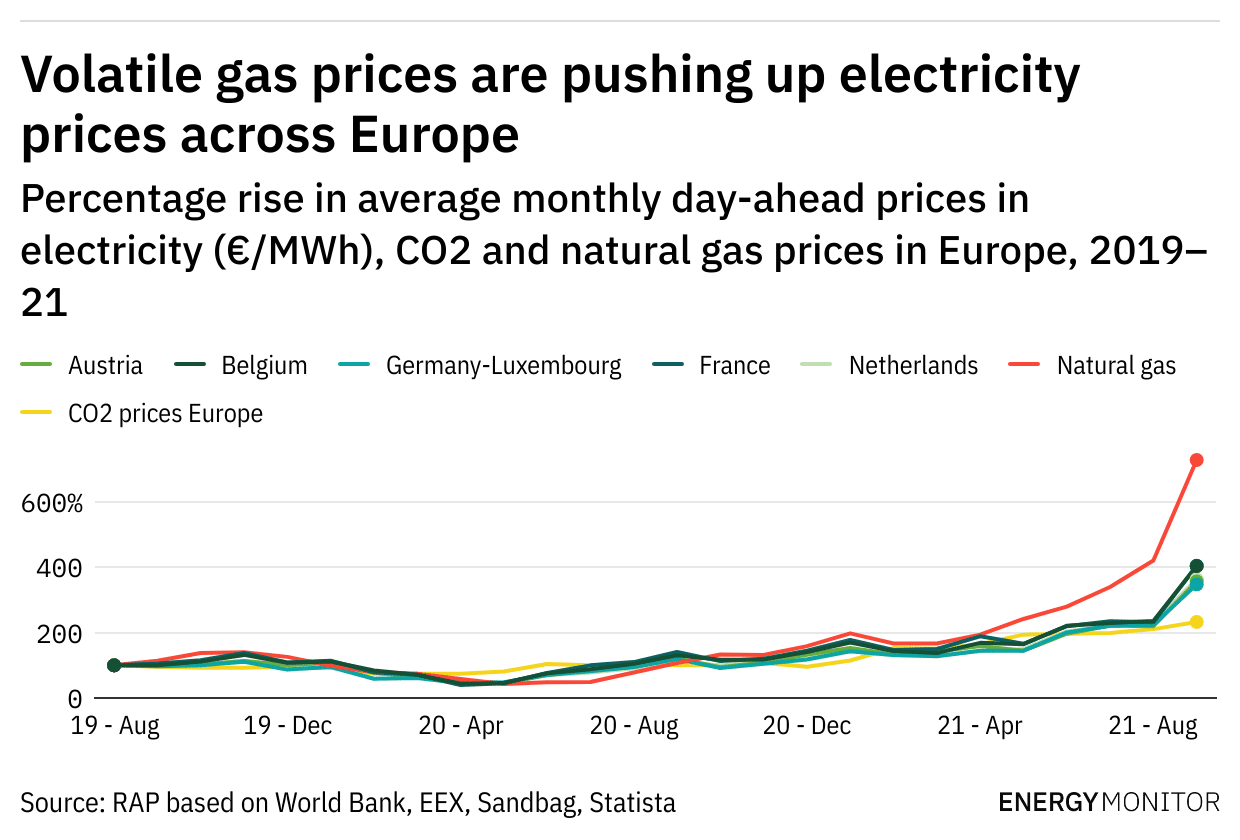

When the global economy picks up steam, so do commodity prices. Gas demand bouncing back to pre-Covid levels started a new upswing in the price cycle. We are seeing classic market dynamics at work: demand outstrips supply and prices rise. Electricity and gas prices are skyrocketing from last year’s pandemic-induced depths, leaving people reeling.

Experts have come to a clear consensus: the surging international demand for natural gas is the overwhelming cause of today’s market upheaval.

What should governments do next? Is there a way to slow down the roller coaster – or, better yet, to get off? To do so, we need both near and long-term solutions.

Winter is coming

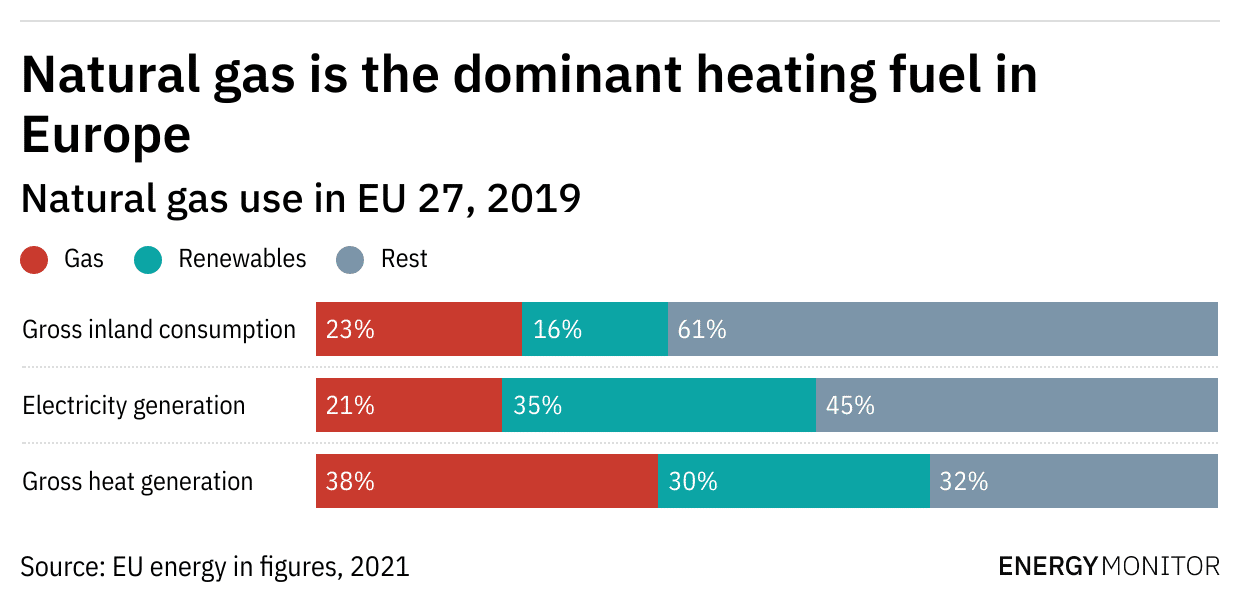

With winter around the corner, the heating season is a particular concern. In Europe, 50–125 million people are already unable to afford proper indoor thermal comfort. Natural gas is the dominant heating fuel in Europe, accounting for 45% of household energy for heating. Rising gas prices may mean dire times for households, especially if the winter is harsh.

Most will agree that panicked reactions are the last thing we need right now, but while governments are rightly preoccupied with short-term measures to help their constituents, there is a risk they will adopt the wrong ones.

Governments across Europe are scrambling to find ways to help families who are struggling pay their energy bills this winter. Most of these measures require funding. Fortunately, governments have a few possible sources of revenue at their disposal:

EUEmissions Trading System (ETS) revenues: Higher ETS prices result in growing auction proceeds – potentially exceeding €50bn in 2022. Using these additional revenues to support consumers would be a prelude to the Social Climate Fund included in the Commission’s ‘Fit for 55‘ proposals for EU ETS reform.

Value-added tax (VAT) revenues: VAT revenues increase proportionally with surging gas and electricity prices, a windfall for government coffers. High energy costs, however, put pressure on household budgets, which can lead to lower expenditure on other consumer goods. Careful analysis of the likely net VAT revenues is needed.

Windfall profit clawback: A more contentious option considered in Spain is to recover possible windfall profits from legacy zero-marginal-cost resources, such as nuclear or hydro. One drawback is that retroactive changes may heighten a sense of regulatory risk and increase the cost of capital.

The focus of government action should be on those who are most affected by the surge in commodity prices: vulnerable consumers. Un-targeted measures, such as lowering VAT rates, may offer advantages in terms of simplicity and transparency, but they will dilute the effectiveness of government action. Targeted measures are more cost-effective. After all, they help only those who need it.

The focus of government action should be on those who are most affected by the surge in commodity prices: vulnerable consumers.

However, the targeting must be appropriate. Again, there are various options available, ranging from lump sum payments, to levy exemptions for vulnerable consumers, to progressive charges on increasing blocks of consumption. While logistically challenging, it is also worth exploring a roll-out of ‘rapid response’ efficiency programmes for specific groups, such as the energy poor or vulnerable. Any energy savings would extend beyond the current crisis.

It is simple: Get off gas

The current crisis is a clear reminder of why the energy transition is so important: removing fossil fuels from the equation removes consumers’ and economies’ exposure to their extreme price volatility.

Most experts expect prices to remain high through the winter. Analysts suggest a potential pickup in liquefied natural gas and pipeline supply may relieve the pressure on gas prices in spring. High price volatility, however, has long been, and will very likely remain, a feature of fossil fuel markets. Given the multiple factors that will affect future natural gas prices – CO2 prices, more volatile energy demand, producer uncertainty about future demand, the costs of maintaining legacy transportation and storage infrastructure, global shifts from coal to gas, and so on – the level of unpredictability will likely only increase.

The best and most durable solution to mitigate the social and economic impact of volatile gas prices is tackling demand for fossil gas. There are multiple good solutions here, all of which must be pursued.

First, energy efficiency must be the top priority. Energy efficiency programmes have demonstrated that large reductions in energy demand can be achieved, thereby lowering dependence on fossil fuels and reducing the risks associated with their price volatility. As part of this, policymakers should seek to electrify end uses that are currently served by natural gas in the buildings sector. Buildings can be weaned off natural gas through the rapid deployment of heat pumps, supported by a package of policy measures including subsidy programmes, regulation and energy price reform.

European policymakers must ensureequity in the energy transition.

Second, the EU should target a massive roll-out of solar and wind power with a goal of net-zero emissions in the European power system by 2035, as advocated for by the International Energy Agency. Wind and solar are increasingly the cheapest power generation resources and already save Europe billions in gas import costs. To reduce the need for fossil gas backup, variable renewables can be combined with energy efficiency and demand side flexibility. Meanwhile, better use of transmission networks and integrated markets will buffer fluctuating renewable resources across larger regions.

Third, European policymakers must ensure equity in the energy transition. With millions of people living in energy poverty, governments must ensure the costs and benefits of the transition are shared fairly among consumers. They should address energy poverty by designing fair network tariffs. Carbon revenues can be earmarked for investments in renewables and efficiency, as well as bill support for vulnerable customers. Enabling access to energy services can unlock bill savings for low-income families.

Is the market broken?

Surging electricity prices have stimulated calls to ‘fix Europe’s broken electricity market’, for example by replacing the current market design with an undefined approach to average cost pricing, which was more common before power markets were liberalised across the continent from 1996.

These attempts to blame market design miss the mark, however. The problem is the cost of fossil fuel, upon which the system remains critically reliant. The European electricity market design is based on sound principles. Until recently, the market produced results that led to calls from governments and investors for increases in wholesale market revenues, either directly through higher energy prices or indirectly through capacity remuneration mechanisms. The current price surges should be seen in this context, as another part of the cycle.

While the European electricity market can definitely be improved, tinkering with its underlying design as Spain, France and other members states are proposing would leave the root causes of the current situation untouched. It could even exacerbate them, and have wide-ranging and potentially adverse consequences. Making price formation un-transparent, and distorting investment signals, could increase instead of decrease costs to consumers. Moreover, triggering an extended period of change and uncertainty would chill new investment and merely exacerbate supply shortages.

Our certainty is this: as long as we maintain our reliance on fossil gas we will stay on this roller coaster. Volatility is inherent to fossil fuel markets, which goes for gas as much as it does for oil. So let’s get off and save ourselves a ton of money, stress and carbon emissions.

A version of this article originally appeared in Energy Monitor.