Energy consumption in the EU is rising despite targets to reduce demand across Europe. This should not come as a surprise and is explained mainly by GDP growth, writes Samuel Thomas.

It’s 1992. The Republicans have been in the White House for 12 years. President George H. W. Bush Sr. has overseen victory in the Cold War and a wave of optimism for the future is sweeping across the world. What could possibly unseat a sitting president in these circumstances?

“The economy, stupid.” It was during the 1992 presidential campaign that this now ubiquitous phrase was coined by James Carville, lead strategist for the Democratic Party contender, Bill Clinton. The first Bush presidency had been plagued by an economic recession and a spike in oil prices caused in part by the Gulf War. George Bush Sr. lost his second bid and became the only one-term US president since the 1970s.

Jump forward to 2019 and the latest data show that EU energy consumption is rising despite targets to reduce demand across Europe. This should not be a surprise: again, it’s the economy. Between 2014 and 2017, EU gross domestic product grew at its fastest rate since the mid-2000s and, however much we would like to kid ourselves, economic activity is not yet meaningfully decoupled from energy consumption.

Faster economic growth has seen rises in industrial production across all sectors, more transportation of goods, and an increase in passenger travel.

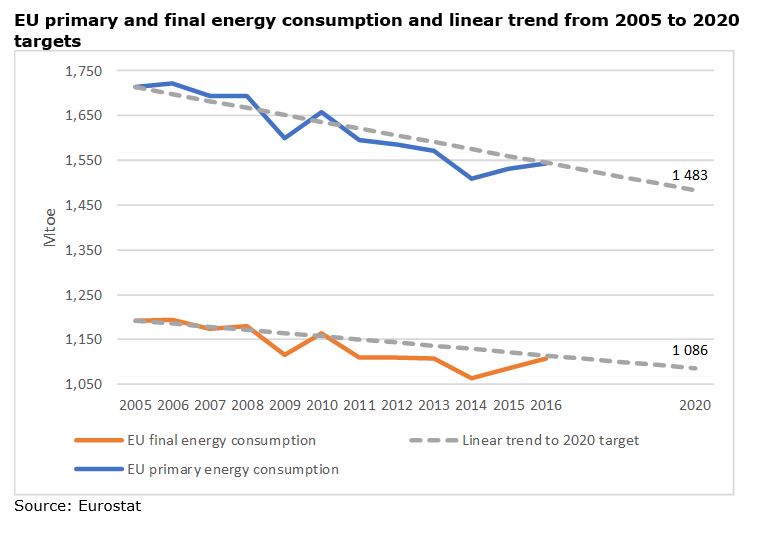

What does that mean for the EU’s 2020 energy efficiency targets? To meet them, final and primary energy consumption must fall by 0.5 percent and 1.0 percent per year, respectively, between 2016 (our latest data point) and 2020. However, over the two years prior to 2016, final energy consumption grew by more than 4 percent and primary energy consumption was up by more than 2 percent. Early indications suggest another increase in 2017.

With only a year to go until 2020, the best hopes to meet the energy efficiency targets lie outside of policymakers’ control. Just as economic growth has driven up energy consumption since 2014, the dark clouds of Brexit and the China-US trade dispute may too cause a downturn in consumption next year. Indeed, both the German and French economies have seen slower growth during the second half of 2018.

The other key factor is the weather. Around one-quarter of all EU final energy consumption is used to heat the spaces we live and work in. That share rises and falls with variations in the weather. A historically warm winter looks to be the most likely way that the targets can be met.

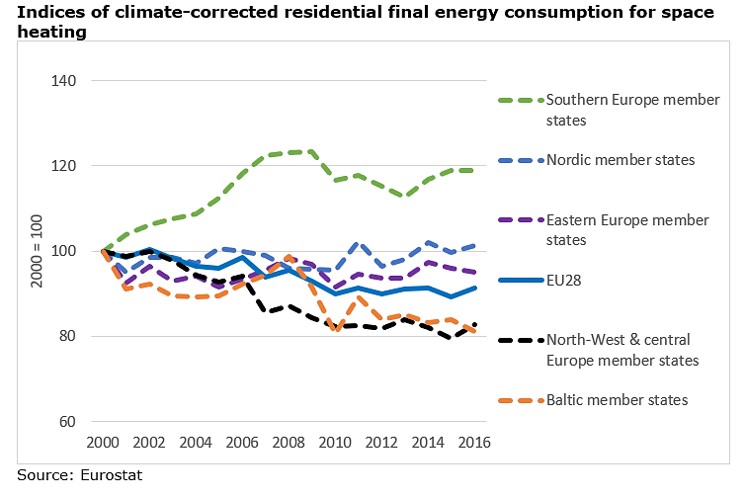

While the weather can have a big impact on yearly variations in energy consumption, energy efficiency gains are what drives it down in the long run. This was the case with space heating in the 2000s (see chart below) as gas condensing boilers replaced conventional gas and oil boilers.

Energy efficiency policies, such as minimum standards for new boilers, and financial incentives drove this trend. However, this decade climate-corrected residential space heating energy consumption (the amount of energy we use to heat our homes, adjusted to take account of winter temperatures) has remained stubbornly stable across all regions of the EU.

Another step change in ambition on buildings efficiency is essential as we look forward to 2030. Kick-starting a new wave of energy efficiency improvements in space heating means upping the rates of building renovation and the installation of more efficient heating technologies such as heat pumps.

Make no mistake—it will not be easy. It will require more investment, both public and private, better evaluation, monitoring and verification, and policy innovation to overcome long-standing barriers to action. Thankfully, the current situation provides the perfect opportunity to act. We have the money, and there is plenty to learn from recent experiences in different countries.

As EU carbon allowance prices rise, auction revenues from the EU emissions trading system are likely to top 10 billion euros per year by 2020. Investing those revenues in building efficiency makes sense for several reasons. Many EU countries are implementing new policy instruments, including energy efficiency obligations. If designed well, those instruments will drive extensive investment in building retrofits, which will in turn deliver a host of benefits: households will benefit from the measures, reducing natural gas imports improves the EU’s energy security, and electrifying heat load will provide more flexibility to the grid as renewable sources increase their share.

A raft of policy innovation is taking place across the world. The U.K., France, and Canada are introducing minimum energy efficiency standards for privately rented properties. Several U.S. states are allowing property improvement loans to be collected through local property taxation. The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative—a carbon cap-and-trade mechanism in New England—recycles 80 percent of its revenues through the funding of additional greenhouse gas abatement, of which around 70 percent is spent on energy efficiency measures.

Fast forward to 2032. Eurostat has just released the 2030 energy consumption data. Will we be celebrating the achievement of the EU’s ambitious energy efficiency targets? Well, in 1992 James Carville wrote three phrases on the sign that hung in the Democratic Party’s “War Room.” The first was most prescient—it would be adapted by the future President Obama on the 2008 campaign trail—and still today most apt: “change versus more of the same?”

Changing up—indeed, dramatically ramping up—our ambitions for energy efficiency is the one surefire way to ensure that we’re not still talking about “the economy, stupid” in 10 years’ time.

A version of this article was originally posted on Euractiv.