In 2013, Marty Kushler, senior fellow at the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), gave a presentation in Chicago on gas efficiency programs. He argued that one should not make decisions about programs with lengthy multi-year effects based on the record-low spot market prices for domestic natural gas. Gas at that time was $2 per thousand cubic feet (Mcf), due in large part to shale gas production from early high-production sites, price support of dry gas from high wet gas and liquids prices, and natural gas energy efficiency programs.

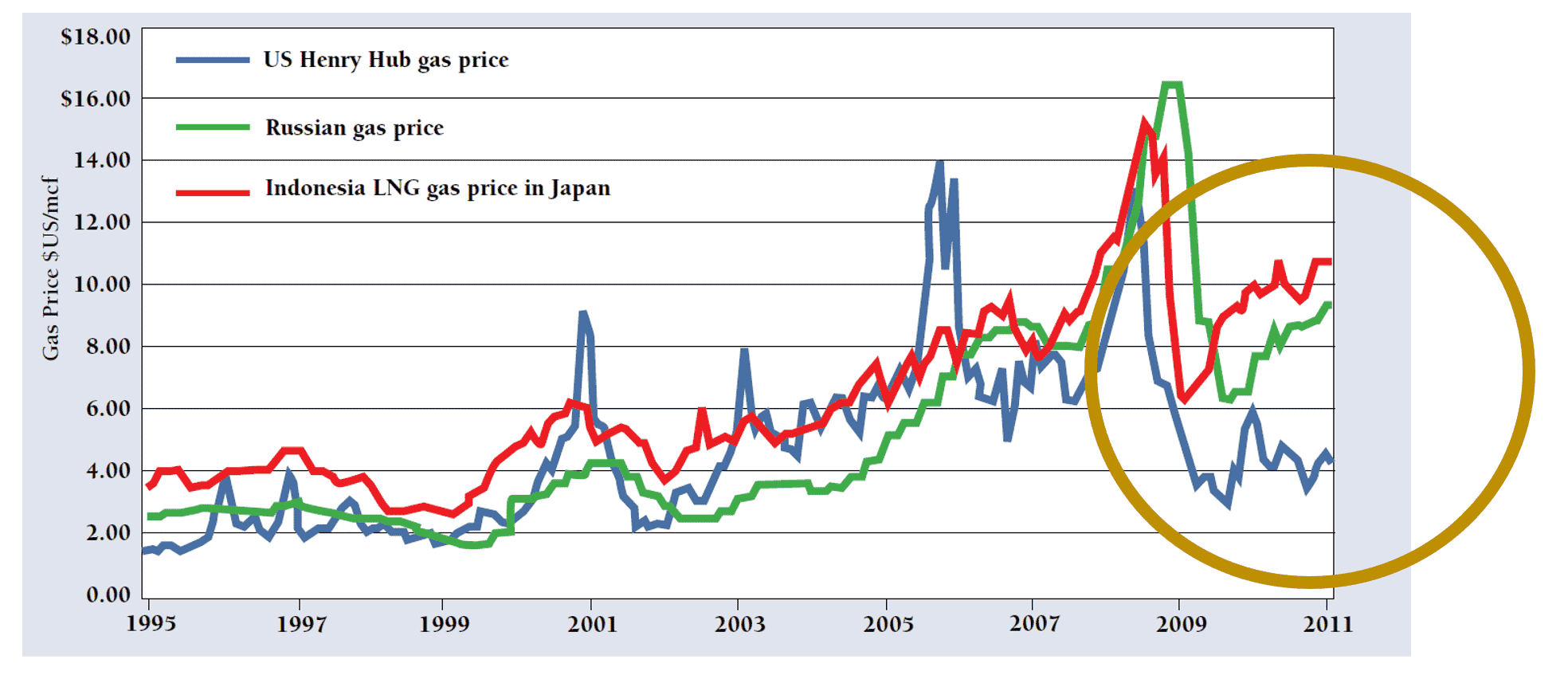

Although in the late 1990s and early 2000s international prices — illustrated below by Russian gas prices and Indonesian liquefied natural gas (LNG) prices — tracked U.S. prices closely, in 2009 domestic and international prices diverged. In October 2013, when European gas was about $11 per million British thermal units (MMBtu) and Asian gas was roughly $16, U.S. prices were a little below $4.

As illustrated below, Kushler referred to this gap as the “Jaws of Delusion” — the delusion being that the United States would continue living with very cheap natural gas while the rest of the world pays three to four times the price.

U.S. vs. Global Fossil Gas Prices (1995-2011)

Spring 2022: Prices Surge

Fast forward a decade to 2022. In April, U.S. natural gas prices reached their highest level in more than 13 years — a surge due in part to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In May, the Financial Times reported that Henry Hub natural gas benchmark reached a price ($8.41 per MMBtu) more than double the price at the start of the year and nearly three times the roughly $3 per MMBtu average of the prior 10 years. In June, the American Gas Association reported that prompt-month futures at the Henry Hub reached $9.32 per MMBtu, noting that “Henry Hub had not seen such prices for prompt-month futures in over a decade.”

Despite this surge, these domestic prices are still far below those in Europe and Asia: $37 and $23 MMBtu respectively. But could that be about to change?

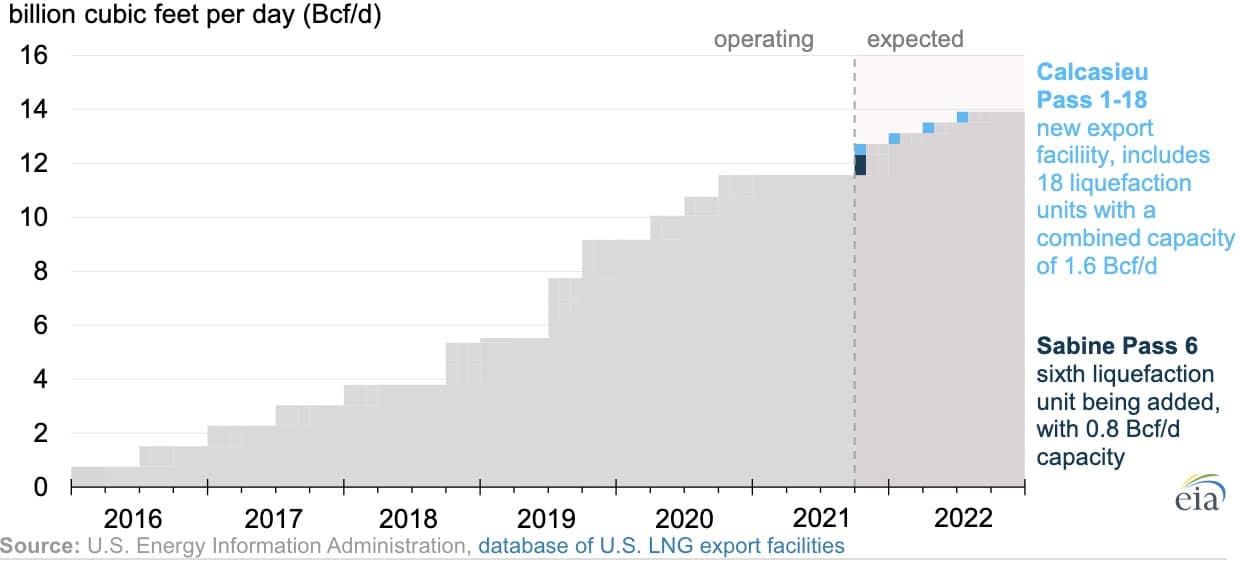

The United States started to export LNG from the lower 48 states in early 2016. We became a net exporter a year later. In 2019, we became the world’s third largest LNG exporter, behind Australia and Qatar. And once new LNG liquefaction units in Louisiana — Train 6 at Sabine Pass and Calcasieu Pass LNG export facilities — are placed in service by the end of 2022, the US will become the world leader in LNG export capacity.

U.S. Quarterly LNG Peak Export Capacity (2016-2022)

Summer 2022: Why We Need a Plan

So was Marty Kushler mistaken? Not about planning.

Planning programs with lengthy multi-year effects based on spot market commodity prices — even with 2013’s record-low US spot market domestic gas prices — would have been a mistake. When he made his point, gas was $2 per Mcf. Two years later it was twice that. And today, 10 years later, prices are three or four times that.

Gas prices are not only uncertain, but that uncertainty is not “symmetrical.” History, Kushler argued, has shown that there is greater risk of prices increasing.

Nor was he wrong about what he called the “largest factor affecting cost not being taken seriously,” namely the potential effects of global gas prices on the U.S. domestic market. In 2013, when Kushler made his remarks, Russia hadn’t invaded Ukraine; U.S. LNG export capacity wasn’t about to dominate the world market; nor was there the ravenous worldwide demand for LNG that we have today.

In a little over six years we’ve gone from being LNG importers to the doorstep of becoming the world’s leading LNG exporter. How can international demand for our domestic commodity not affect its value, especially given current conditions and winter on the way?

In June we had a clear demonstration as to the effects that international demand for LNG will have on the prices that Americans will be paying for gas. There was a fire at the Freeport LNG plant in Texas, our nation’s second largest LNG export facility. The accident and the resulting outage produced a sharp reduction in export demand for domestic gas, producing a 40% reduction in U.S. domestic prices through early July. So, what will happen when Freeport comes back online, and the U.S. domestic market begins feeling the demand pulling in the other direction?

The Jaws of Delusion: The Summer 2022 Blockbuster We All Want to Miss

In “Jaws,” Roy Scheider’s character who had just been face to face with the great white shark tells Captain Quint, “you’re going to need a bigger boat.” That might have solved their problem. But a bigger boat is not going to help with the Jaws of Delusion. We are already in a big boat — the global market for gas. That‘s the point: How can U.S. consumers escape the effects of international demand for our gas?

There are steps that regulators can take, given this looming uncertainty for domestic gas prices. How about starting with the one implied by Marty Kushler a decade ago: Let’s stop relying on one resource, and instead, diversify to reduce the exposure of utility customers to the uncertain prices and volatility of gas. This, of course means enabling alternatives:

- Building weatherization, for example, continues to provide significant savings for consumers. It also puts Americans to work in our communities and keeps energy investment dollars local.

- Electrification for cooling and heating is another alternative. Despite electricity prices, heat pumps and heat pump water heaters are three times more efficient than other gas end uses. This is one of the reasons that in late 2021, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency decided to suspend ENERGY STAR Most Efficient recognition of gas appliances. Making efficiency available to consumers in the form of better building envelopes and appliances means making savings available.

This is a good time for utility regulators to reconsider the wisdom of allowing subsidies for gas system buildouts. Given what we know, does it still make sense to encourage gas system expansion? If electric options are cheaper and economically more attractive for consumers, why continue to put more pipe in the ground?

There are other steps that regulators and policymakers can take to protect their citizens’ exposure to gas prices, for example, coordinating planning assumptions around gas and electricity. Instead of letting gas and electricity utilities separately model the future, explore their use of common assumptions in order to be able to make apples to apples comparisons with the resources each provides.

To help incorporate voices from underserved and overburdened communities, states should remember to undertake planning in ways that engage the public to better ensure realistic assessments of the least risky options to heat and cool homes, especially homes of energy burdened Americans.

Today, more than any time in our recent history, energy security is a global challenge. Ironically, many of the solutions to this challenge can start at home. In fact, with the help of utility regulators, they can start in people’s homes.