In the board game Monopoly, an important feature is the ‘get out of jail free’ card, which allows players who end up in jail to avoid paying a fine to get out.

In recent months, gas industry representatives have suggested that, when it comes to decarbonising buildings, hydrogen is their get out of jail free card. They argue that eliminating emissions from buildings is possible by replacing existing heating fuels with hydrogen or other gases without having to insulate the building fabric first.

However, rather than looking to expensive technologies, Europe should focus efforts on insulating buildings to ensure they are as energy efficient as possible. Such an approach would save money, energy and leave green hydrogen from renewables to help decarbonise industries for which there are few other solutions.

Renovation challenge

A transformational change in both the rate and depth of building renovation is needed for Europe to meet its climate targets. The European renovation wave aims to at least double the renovation rate. Analysis by the European Commission suggests the average energy renovation will need to reduce a building’s energy consumption by between 52% and 66% in the residential sector and by more than 40% in the services sector.

This challenge is daunting when compared with the situation today. The average energy savings achieved by renovations were only 9% in residential and 17% in commercial buildings from 2012 to 2016. Deep renovations that save more than 60% of primary energy were only carried out in 0.2–0.3% of the building stock each year. This is far from enabling Europe to meet even its 2030 climate goals.

Given the scale of the challenge, Member States will understandably seek quicker and easier ways of reducing emissions from buildings that do not require renovation. Hydrogen, consumers are told, can perform this role. Yet this argument does not stack up. Here are four reasons why.

Why energy efficiency wins out over hydrogen

First, hydrogen is an expensive way of heating buildings. Heating with hydrogen is expected to cost about three times more than fossil gas (even if hydrogen is derived from fossil gas with carbon capture and storage) and twice as much as renewable heating systems. It would increase household energy bills and could push households into fuel poverty.

Heating with hydrogen while failing to reduce heat demand through cost-effective energy efficiency measures is the equivalent of “ forcing limousines onto people who cannot afford a car”, suggests Brian Vad Mathiesen, professor of smart energy heating at Aalborg University, Denmark.

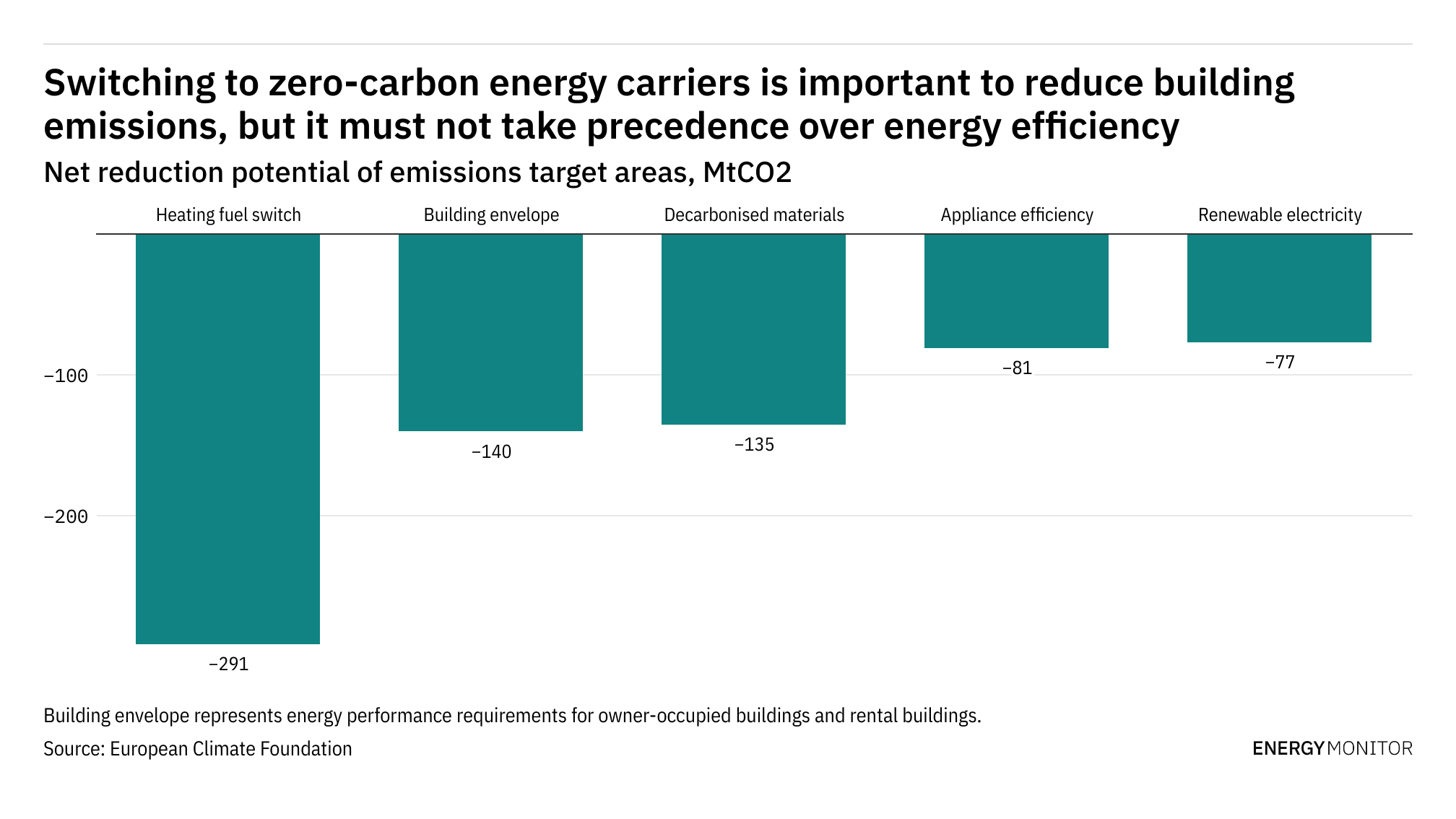

Second, most, if not all, independent analyses of low-carbon pathways rely on energy efficiency to deliver significant emission reduction. Up to a point – and we are nowhere near this point – it is cheaper to reduce demand through insulation than to supply decarbonised heat. In other words, without energy efficiency, the total cost of decarbonising heat will skyrocket.

It is cheaper to reduce demand through insulation than to supply decarbonised heat.

Third, some hydrogen proponents claim that, for renewable heating technologies such as heat pumps, insulation is needed whereas for hydrogen boilers it is not. That argument is false. It is possible to heat an uninsulated building with an oversized heat pump operating at higher flow temperatures, just as it is possible to heat it with hydrogen. The reason for improving building fabrics, however, is that any heating system, whether fossil fuel-based or renewable, will operate more efficiently and at lower cost in a well-insulated building.

Singling out heat pumps that are typically designed for much lower flow temperatures is disingenuous. They can be designed for and operated at higher flow temperatures. However, it would result in unnecessarily high energy use and high running costs, as would using hydrogen in uninsulated buildings.

Fourth, the potential of untapped cost-effective energy efficiency improvements in Europe is still vast. The German Fraunhofer Institute estimates 25% of residential heat demand could be cut through cost-effective insulation measures alone. Cost-effective means the measures pay for themselves – they save more money than they cost to install, benefitting consumers and society.

Ticking all the boxes

Deciding not to deploy cost-effective energy efficiency measures violates the energy efficiency first principle at the heart of the European energy transition, as defined by the European Commission. In turn, this also creates an economic liability in the form of higher running costs, unnecessary investment in energy supply infrastructure and fewer of the well-known multiple benefits of energy efficiency.

The bottom line is that hydrogen, as a replacement for energy efficiency actions, is likely to force consumers into a more expensive way of heating and leave them with leaky and inefficient buildings. Using hydrogen as a get out of jail free card to avoid renovating buildings could lock us into an unnecessarily expensive energy future.

A version of this article originally appeared in Energy Monitor.