The urgent tone of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s sixth assessment report, published on the ninth of August this year, shows the clear and stark need for immediate and rapid greenhouse gas emission reductions. Globally, across the EU and in the UK, heat pumps are seen as a vital technology to remove emissions from heating where fossil fuels currently dominate. The UK government has a target of 600,000 heat pump installations a year by 2028, and advisors to the Climate Change Committee have suggested an even higher figure may be needed based on their balanced pathway.

With the global market for heat pumps set to rapidly expand, investment opportunities for heat pump manufacturing are clear. And for the UK, which is one of Europe’s largest heating appliance manufacturing bases, albeit based around fossil fuel boilers, the potential is particularly obvious. Heat pumps and boilers are made from similar raw materials, use many related parts and share a very similar supply chain.

But despite the UK being well positioned to benefit, the existing piecemeal policy support — and the impending policy gap beyond the closure of the domestic Renewable Heat Incentive — puts not just UK climate targets at risk, but risks the UK losing wider industrial benefits which could be realised by growing heat pump expertise rapidly and early.

The UK government could offer a major industrial boost by using the upcoming heat and buildings strategy to clearly spell out the timeline for a fossil fuel boiler ban in new homes, to provide details of the upcoming grant scheme and to outline a plan for achieving a fossil fuel phase-out date.

Pumping up the baseline

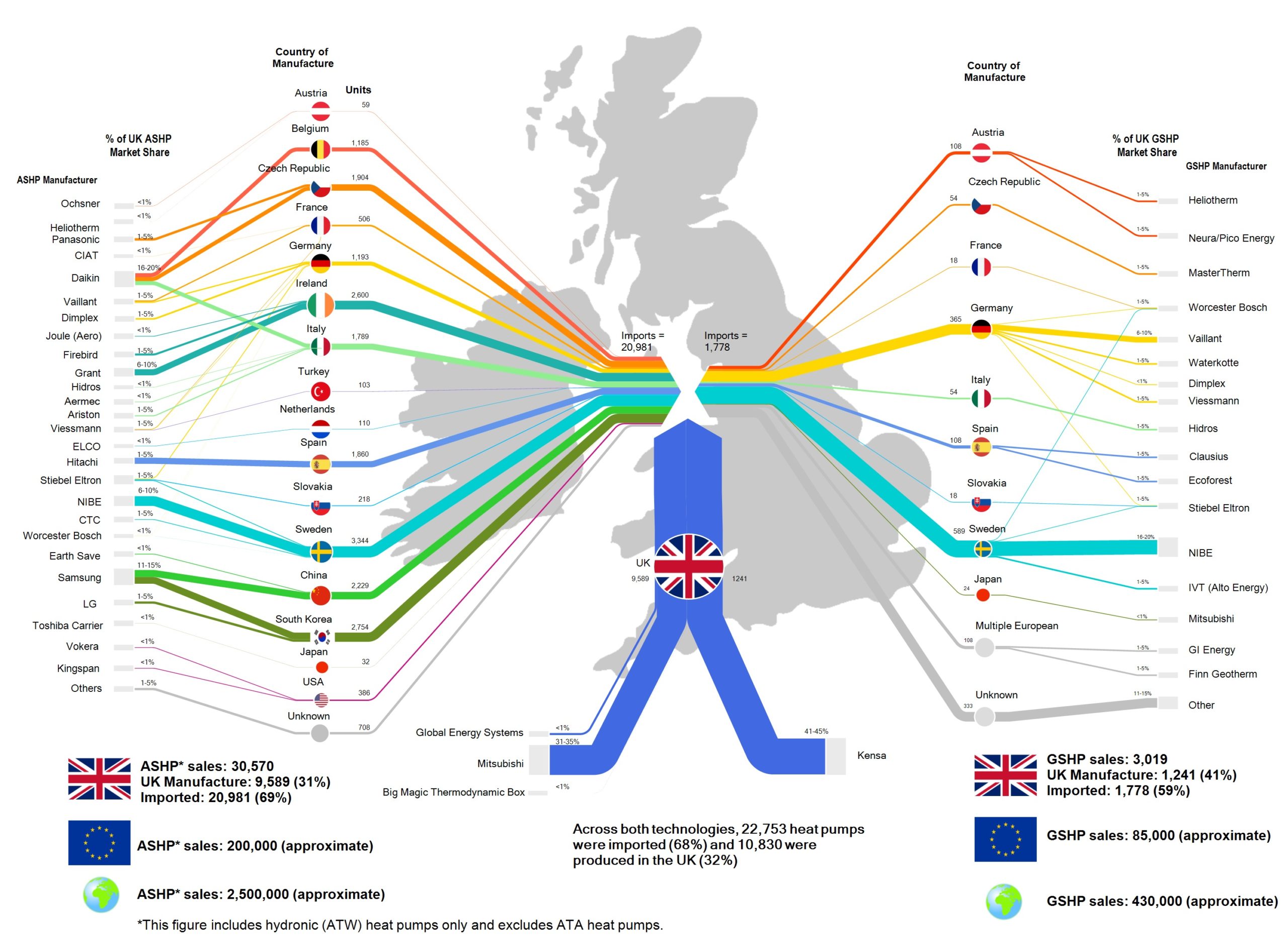

Heat pumps are already manufactured in the UK; the Cornish-based company, Kensa, is a key player in the market for ground source heat pumps, those that extract heat from the ground. Last year, institutional investor Legal & General took a 36% stake in Kensa Group as part of their net zero investment programme.

When it comes to air source heat pumps that extract heat from the air, Mitsubishi has been manufacturing its ‘ecodan’ models in Livingbridge in Scotland for more than a decade. Aside from Kensa and Mitsubishi, around two-thirds of all heat pumps are currently imported according to analysis for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). This figure excludes air-to-air heat pumps which are often used for cooling.

If the market for heat pumps does grow, as it must, it makes sense to encourage the development of UK-based manufacturing, particularly if the UK market for boilers slows down. Developing a manufacturing base early could reduce the risk of further losing out to imports and deliver high value growth, high-tech jobs and potentially create a strong export market supporting ‘just transition’ goals around high quality green jobs.

Some new green shoots are emerging. In June, Vaillant announced that it will start manufacturing air source heat pumps in the UK beginning next year alongside its boiler production lines in Belper, Derbyshire. Notably, Vaillant also led the UK’s heating appliance market towards condensing gas boilers, suggesting others may follow in their heat pump path.

In general, most of the UK-based oil and gas boiler manufacturers also sell heat pumps, or are part of wider energy groups that include heat pump businesses. Far from heat pumps being a threat, these companies may be able to respond easily to market signals, taking their business and employees from boilers to heat pumps.

Beyond boxes

Because the initial installation of a heat pump takes longer than a gas boiler swap, the growth of heat pumps implies an increase in the required number of heating engineers.

Innovative UK energy supplier Octopus is already starting to develop in-house heating pump skills having recently set out plans to train 1,000 in-house engineers each year. In addition, the UK Heat Pump Association has announced that a new course will be able to train installers at the rate of 40,000 per year.

These early signs are positive, but only a market growing over the longer term will lead to these training centers being filled and will create a clear pull into the sector. Concerningly, the existing heating workforce is also shrinking and set to shrink further, with fewer people entering the industry each year. Because of the time it takes to become a skilled heating engineer, an active focus on skills seems like a policy necessity.

Policy certainty will drive investment

The upturn in the UK heat pump market last year, cited by Vaillant as part of the reason for their investment, reflects short-term policy changes. These include an increase to the Renewable Heat Incentive tariffs in 2018, the extension of the scheme to April 2022 as well as a number of temporary schemes, which were part of the Covid response package, including the ‘public sector decarbonisation scheme’ and the ‘local authority delivery scheme’ (as well as the now-closed Green Homes Grant). There is no evidence, however, of a long-term demand increase, and investments have been carried out in good faith. A significant policy gap for domestic heat pumps is already on the horizon, starting in April 2022.

BEIS’s analysis on UK heat pump manufacturing and supply chains highlighted that appliance manufacturers would require a ‘clear strategy and commitment from government, including future policy that is consistent and designed for the long-term, not short term, and providing clarity on the need for heat pumps’ and a ‘stable regulatory system’ in order to invest in UK heat pump manufacturing facilities. The theme of policy certainty is also central in the interim report of the Heat Pump Sector Deal Expert Advisory Group in Scotland.

Progressing policy

The UK government can take some simple steps to provide support to the fledgling, but clearly eager heat pump industry.

Firstly, the 2025 ‘Future Homes Standard’ for new houses must not slip. Legislating for the fossil fuel heating ban earlier than 2024, as proposed in the January consultation, would provide certainty for the industry and reduce the risk of further delays. Government intent on this should be clearly spelled out in the heat and buildings strategy because this policy would drive a clear upturn in the heat pump market.

Secondly, the heat and buildings strategy needs to be thorough, transformative and — most importantly — published as soon as possible. While legislation is important, a clear government sign within the heat and buildings strategy on the direction of travel would provide valuable ‘soft’ political support for the industry.

Thirdly, a commitment on financial support is required. Capital grants are likely to be the easiest option for both households and the government in the short term. However, the ‘Clean Heat Grant’ as consulted on, would not provide the required level of support to meet the government’s own targets. A boost to funding alongside confirmation of details, including timing and support levels, would provide a valuable market boost.

The heat is on for the UK government, particularly in the run up to the Glasgow Climate Change Conference in October and November. While there is lots to do beyond heat pumps, heat decarbonisation policy doesn’t need to be complex. Through providing businesses with certainty, the market will grow, innovation will take place and eventually the industry will be strong enough to support itself.

A version of this article originally appeared in Business Green.