The changes underway in the electricity industry are well documented: Demand is flat or declining; renewable energy and storage technology costs are plummeting; utilities and third parties are offering customers new technologies and services; and the need to cut emissions is increasing. And there’s a growing recognition that adapting to these changes requires new regulatory approaches.

Why can’t our traditional approach to regulation tackle these new challenges? A key reason is that it was primarily designed to get utilities to build out the power grid and provide universal access to electricity — key public policy goals of the early 20th century. The traditional cost-of-service model, which rewards utilities for increasing sales and capital-intensive solutions to grid needs, served those original goals admirably. But it stands as a barrier to achieving other outcomes that society now cares about. Public policy aims have shifted since the early 20th century, and increasingly states want to focus on other goals such as system resilience, consumer empowerment, affordability and emissions reductions. This has resulted in a rethinking of how we compensate utilities for providing energy services.

As states consider moving to a regulatory model that compensates utilities not on their capital investments but rather on whether they achieve certain defined outcomes — the model known as performance-based regulation — it is important to make sure those outcomes directly benefit the public good. At RAP, we think that means things like better service quality, lower costs, more clean energy and reduced emissions.

All of this sounds like a no-brainer — connecting utility shareholder value to benefits for customers and society. In practice, challenges await states that go down this road, but several are taking steps in this direction. For starters, defining and agreeing on key outcomes can be tricky with a diverse and growing set of stakeholders, but defining priorities can help. The Minnesota and Hawaii public utilities commissions have recently done just that with orders that lay out processes for selecting and prioritizing performance goals and outcomes.

Once goals and outcomes have been chosen, the next steps are to design metrics to track whether utilities and the broader energy system are meeting them and to decide whether to pair those metrics with monetary incentives or penalties. Where the data on these metrics comes from, and whether it is verifiable by outside entities, are also important cornerstones to establish. Determining the best baseline from which to measure progress is also an important element, as are creating a fair way to motivate utilities and avoiding potential unintended consequences.

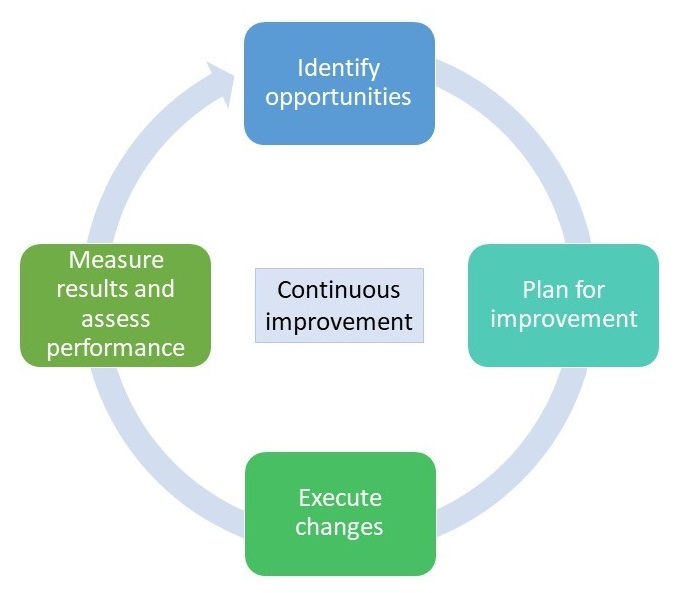

Implementing such significant changes is no small feat for regulators, but fortunately they are well suited to the task. They may have to start, however, by doing something uncomfortable: embracing imperfection. The nature of the challenge — with its technical complexities, imperfect information and constantly changing circumstances — means that getting everything exactly right the first time is unlikely. Instead, we should focus on moving in the right direction while regularly reevaluating our progress. Reforming regulation to meet the requirements of the future will necessarily be a process of continuous improvement.

Taking a hopscotch approach to regulatory reform, where each step validates the last and enables the next, also will make it easier for regulators to include and value the importance of benefits that have been hard to monetize traditionally. Several of these — such as greater customer empowerment, enhanced participation by distributed energy resources and reduced emissions — may in fact be central rationales behind states’ exploration of regulatory reform. By acknowledging that the assessment and achievement of these benefits will require adjustments over time, regulators can encourage utilities and stakeholders to actively engage in this iterative process. In practice, this means periodically revisiting both the goals and outcomes and the metrics and data used to assess whether they are being effectively achieved. This, in turn, will help identify opportunities for improving and strengthening the overall structure.

Although challenges lie ahead in reforming our traditional regulatory paradigm to meet the needs of the future, we needn’t fear that doing so requires a flying leap. Unlike Evel Knievel in his famed motorcycle jumps, we don’t need to clear the chasm all at once. We can use hopscotch to get there instead.