Thanks to an increase in manufacturing development, electricity demand is rising faster than expected in the Southeast. As a result, Duke, Georgia Power and TVA are asking their regulators to approve a series of new gas-fired generators using reliability and low cost as the leading rationale. This has been characterized as a very big ask.

Before approving these investments, regulators may want to ask themselves the following question: “Will natural gas continue to be a reliable, low-cost fuel over the life of the proposed generation fleet?” After all, a gas plant is only as reliable and low-cost as its fuel supply.

To address this question, let’s examine gas supply and demand through three lenses: price volatility, price competition and domestic production.

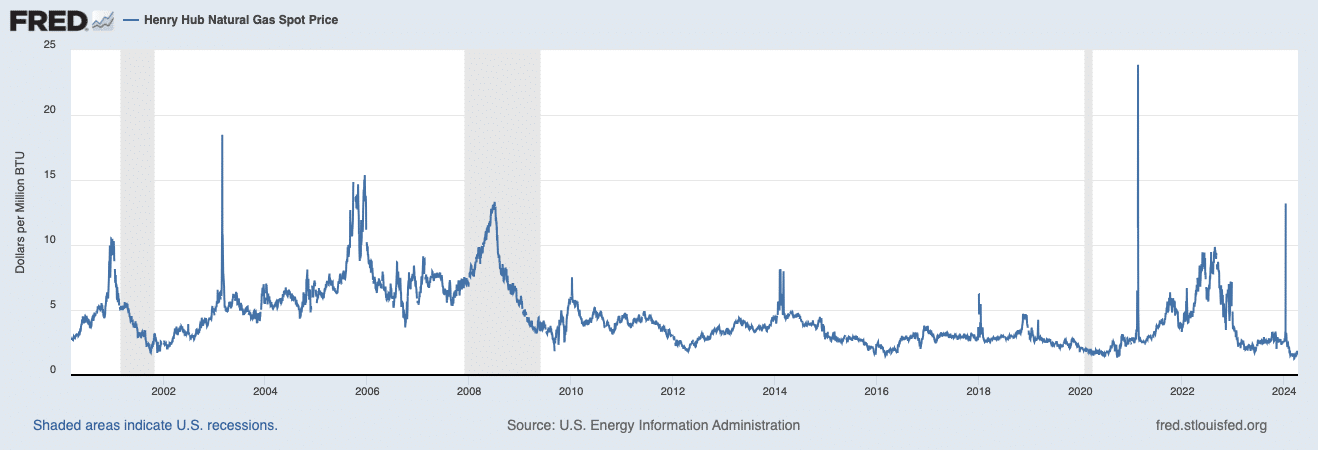

Price Volatility is a Feature of Gas Markets

Historically, natural or fossil gas has been an abundant, domestic fuel source. Aside from its air emissions, its primary downside has been price volatility. In a typical year, gas price volatility fluctuates around the 50% mark. This volatility can sometimes be a boon to consumers, as evidenced by the current price plunge into the range of $1.50 per million British thermal units (MMBtu). However, over the last 25 years prices have breached $15 per MMBtu three times, most recently as a result of the war in Ukraine. This represents a tenfold increase over today’s prices, and illustrates the fact that price volatility is a basic feature of gas markets.

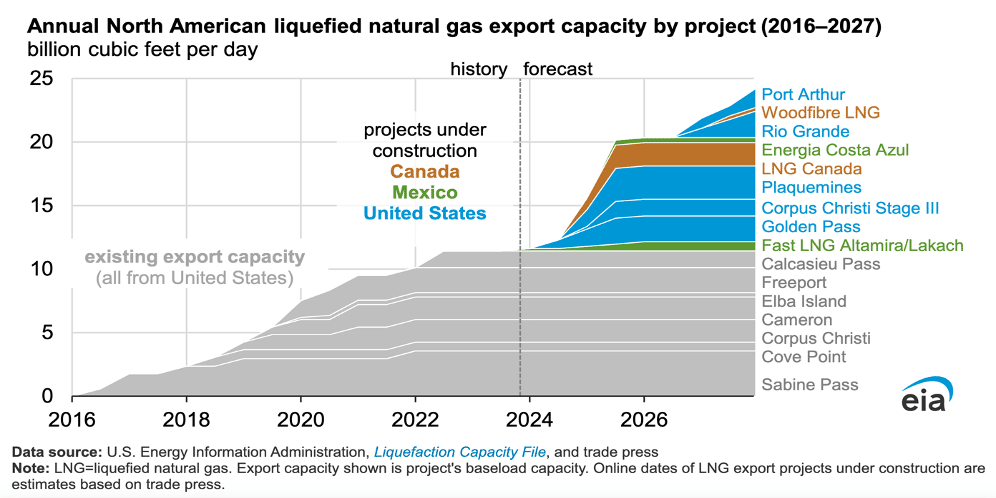

Exports Increase Price Competition for Gas

Thanks to the shale gas revolution, natural gas has become so abundant that is it being exported to other countries, where prices are often as much as five times higher than they are in North America. North America’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) export capacity is set to double by 2027, and will soon consume about 20% of U.S. supplies. As this global market has developed, price competition has increased and the causes of price volatility are no longer limited to events in North America. Global trade, global weather and geopolitical events now affect North American gas prices. This represents a new and substantial change that regulators must consider as they assess today’s proposals to build new gas-fired generation.

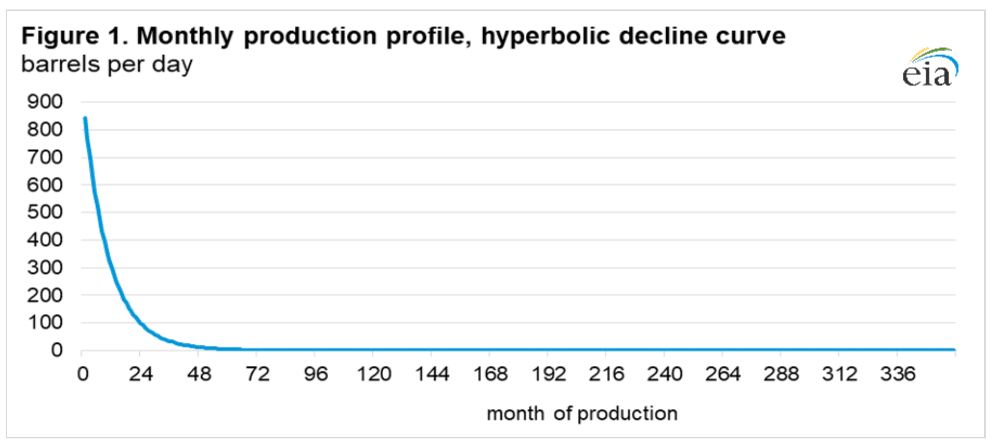

Domestic Production is Maturing

Although shale gas production continues to increase, it has an Achilles heel. Only a month after a well is drilled, production drops off steeply, and at the 24-month mark it is only 10% of the well’s first month’s production. This phenomenon is a fact of life in the oil and gas industry. What makes it troublesome is that well decline rates are increasing. This means that sustaining, let alone growing, shale gas production is getting more difficult as the resource base matures, and it adds uncertainty to the regulator’s decision to approve a gas-fired power plant. Will North American gas supplies be able to meet international demand growth without increasing domestic prices?

Implications

The past decade was characterized by abundant gas supplies that were low-cost, but still volatile. Importantly, exports were de minimis during this period and the geologic resource base (shale) was still young. The coming decades will be characterized by substantial and increasing exports, as well as a maturing resource base. Both of these developments point to a future where natural gas prices are likely to increase and become increasingly volatile. Based on today’s futures market prices, which are higher than today’s spot market prices, this future is already being anticipated.

Wind and Solar, a Price-Stable Alternative

About 70% of a gas plant’s levelized cost comes from the cost of its fuel. Because gas prices are so volatile, this makes estimating the levelized cost of a gas generator difficult. This stands in contrast to solar and wind generation, whose levelized costs are not only competitive with gas, but also mostly fixed at the time of their financing and construction. Fuel price volatility, fuel price competition and fuel production are all non-issues for wind and solar generation. For practical purposes, the variable costs (including fuel) of renewable generation are zero, and there is no international price competition for their “fuel,” wind and sunshine. As a result, the levelized cost of wind and solar resources is more easily estimated, and in contrast to gas, more knowable in advance.

Recommendations

Will natural gas continue to be a stable source of low-cost fuel over the life of the proposed generation fleet? Let’s be fair: We cannot know, nor can we expect a utility to know, the answer to this question in advance. We do, however, know two things.

- First, we know that utilities can hedge the fuel cost risks that their electric customers are expected to bear. As a result, we recommend that utilities analyze the cost of procuring long-term, price-stable gas supplies for their power plants. Using least-cost planning, which Duke, Georgia Power, and TVA have been practicing for a long time, the utilities can show their regulators how the levelized cost of firming up supply for gas-fired generation compares to the cost of wind and solar generation.

- Second, we know that customers bear most of the risk of fuel cost adjustment mechanisms. We recommend that regulators adjust them so that utility shareholders bear the majority of the risk. The rationale for doing this is simple: Customers have no means to hedge fuel price risk, while utilities do.

By adopting these two recommendations, regulators can help ensure that the next generation of power plants are collectively reliable, least-cost and lowest-risk.