In November 2018, the EU General Court ruled in favour of a legal challenge mounted by Tempus Energy to the Directorate General for Competition’s (DG COMP) approval of the capacity market in Great Britain. In its challenge, Tempus successfully argued that, due to serious flaws in the design of the capacity market, DG COMP should have had doubts over its compatibility with State Aid rules and carried out a full “phase 2” investigation before approving the scheme.

Following the General Court’s ruling, DG Comp initiated an in-depth investigation in February of this year. Although such investigations normally last up to 12 to 18 months, some commentators believe that a decision re-endorsing the compatibility of the capacity market with State Aid rules is imminent.

In carrying out its comprehensive assessment, DG COMP not only needs to consider the validity of the original decision but also the need, if any, for a capacity market going forward. Unfortunately, the evidence presented to the Commission by the UK government supporting the continuing need for a capacity market is not in the public domain, the government having prevented National Grid from releasing the evidence.

However, the data generally available suggests that Great Britain has a considerable and increasing surplus of capacity, with no immediate need for new investment. Furthermore, there is no evidence to suggest that a capacity market is necessary to bring forward new investment, should that need eventually arise.

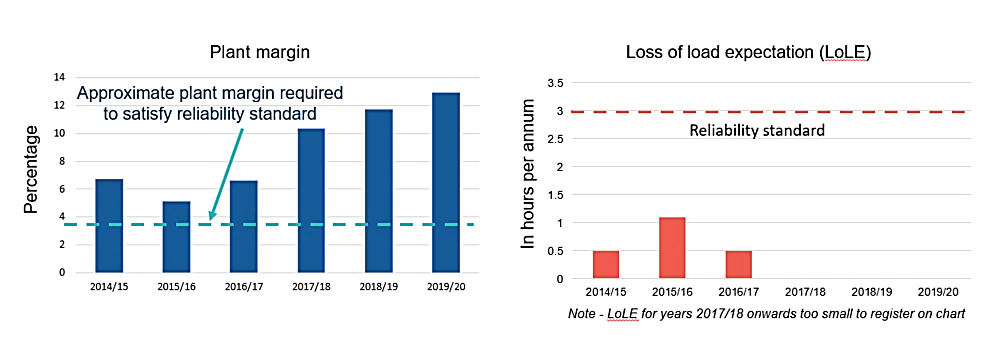

In fact, as illustrated in the chart below, National Grid’s Winter Reviews show that the de-rated plant margin, or the level of capacity above peak demand, has consistently exceeded the reliability standard in Great Britain over recent years. It has reduced peak demand and increased interconnector capacity, more than offsetting the continuing and welcome decommissioning of coal plant.

The impact of these trends is exacerbated by National Grid’s persistent over-estimation of peak demand, a fact highlighted by the independent Panel of Technical Experts, and use of other cautious assumptions. The result is a predicted plant margin of around 13% for this coming winter. In fact, if the de-rated plant margin is calculated as the excess of generation capacity over demand seen at the transmission level rather than total demand, the predicted margin for this coming winter is around 16%. This implicit inclusion of the contribution made by distributed generation suggests a margin that is more than four times that necessary to meet the reliability standard.

Excessive plant margins are a waste of consumers’ money. They place an additional burden on customers through inflated electricity bills, without sufficient value to justify the associated costs.

Let’s assume, for example, a combined cycle gas turbine plant has a new entry cost of 49 pounds sterling per kilowatt to recover its capital investment and fixed costs. The current excess capacity in Great Britain’s electricity market adds approximately 276 million pounds to consumers’ bills every single year.

In addition, paying outside of the energy market for an unnecessary capacity mechanism delivers excessive plant margins. This depresses the energy market signals necessary to develop the flexible resources such as demand response and storage that are vital to the successful transition to a low-carbon electricity system.

Ofgem’s 2019 State of the Market report confirms that imbalance price volatility continues to fall while there has only been one significant spike in prices during the last three years. Yet Ofgem’s report shows that balancing costs in Great Britain are still increasing year on year mainly due to transmission constraints and the growth in intermittent renewable generation outpacing transmission development. New sources of flexibility to manage both the increasing variability of a changing plant mix and the increase in transmission constraints are urgently required.

In recent years, Great Britain has introduced balancing market reforms that should provide the signals necessary to develop those new flexible sources. These reforms are now built into EU legislation via the recast Electricity Regulation as the means of securing electricity supplies without the need for direct capacity support. However, despite these initiatives, the combination of a capacity market and excessive plant capacity in Great Britain is preventing those reforms from doing the job they were intended to do.

We don’t know yet whether DG COMP will once again conclude that the GB capacity market complies with State Aid rules and that, despite ample evidence to the contrary, its continued operation is justified. However, the omens are not good, as the Commission’s opening opinion suggested that it is minded to accept the UK government’s case that a need for additional capacity support still exists.

This would be particularly unfortunate for the reasons expounded above. It would also suggest that the Commission does not intend to implement or enforce the requirement that the energy market reforms set out in the recast Electricity Regulation be relied upon in the first instance to ensure supply reliability without the need for market-distorting capacity mechanisms.

A version of this article originally appeared on Euractiv.