As India looks to “build back better” from the Covid crisis, the country would benefit economically, environmentally and socially by investing in clean technologies.

In late 2019, the Indian government announced a $1.4trn National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP) to jump-start economic growth. This plan includes a high-profile target for the addition of 75GW of thermal power plants by 2025. At a time of overcapacity and low utilisation rates, it makes no economic sense for public or private investors to finance coal power plants in India.

That announcement was before the pandemic. The government is now expected to sharpen its focus on the investments planned in the NIP in an attempt to boost the country’s GDP, which took a huge and unprecedented hit due to Covid-19 lockdowns.

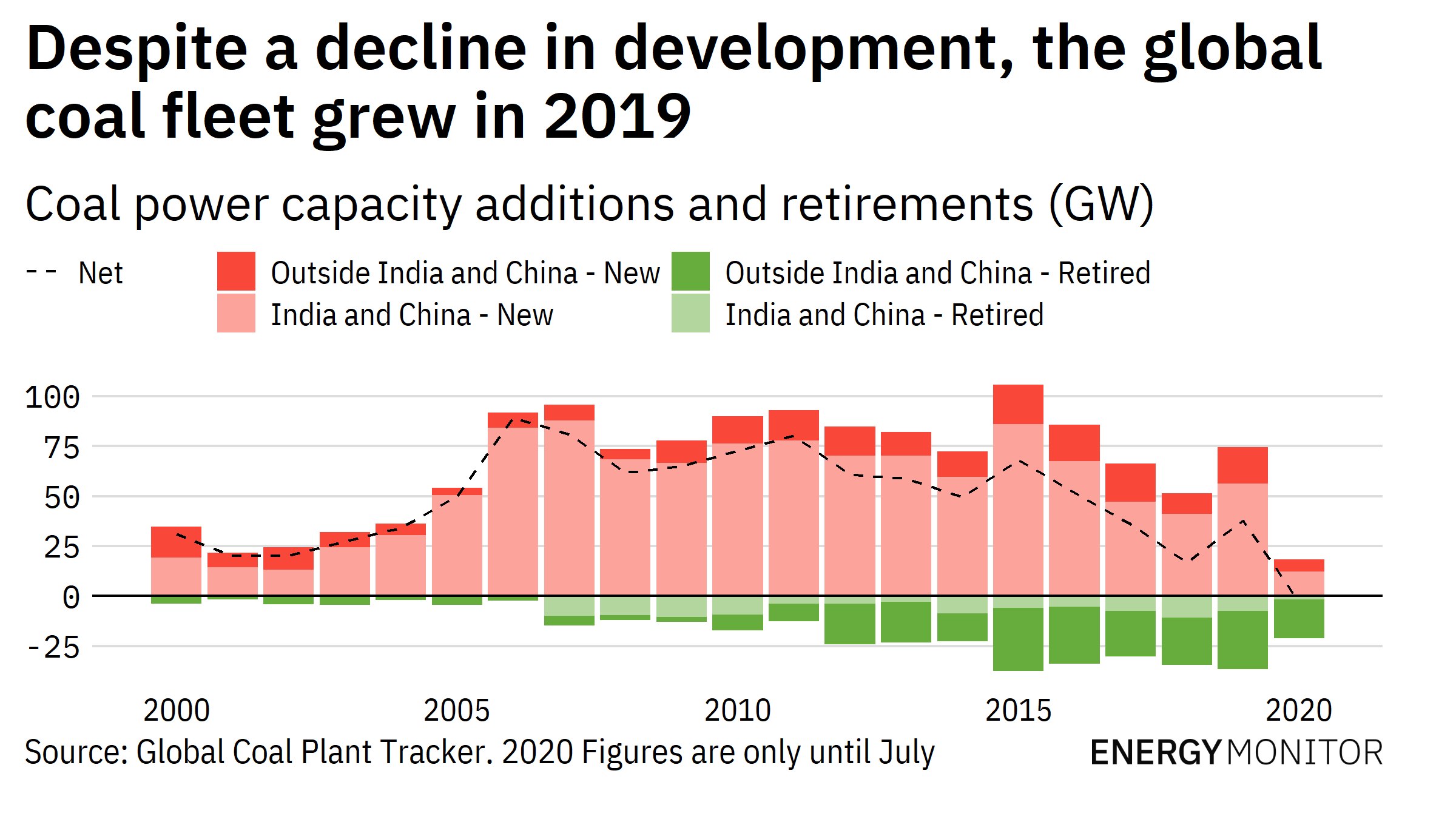

However, both debt and equity investors are wary of funding coal power plants, and the pipeline of new investments in them has shrunk. India’s share of the global coal power development pipeline has fallen from 17% to 12% in the past two years, according to the Global Coal Plant Tracker.

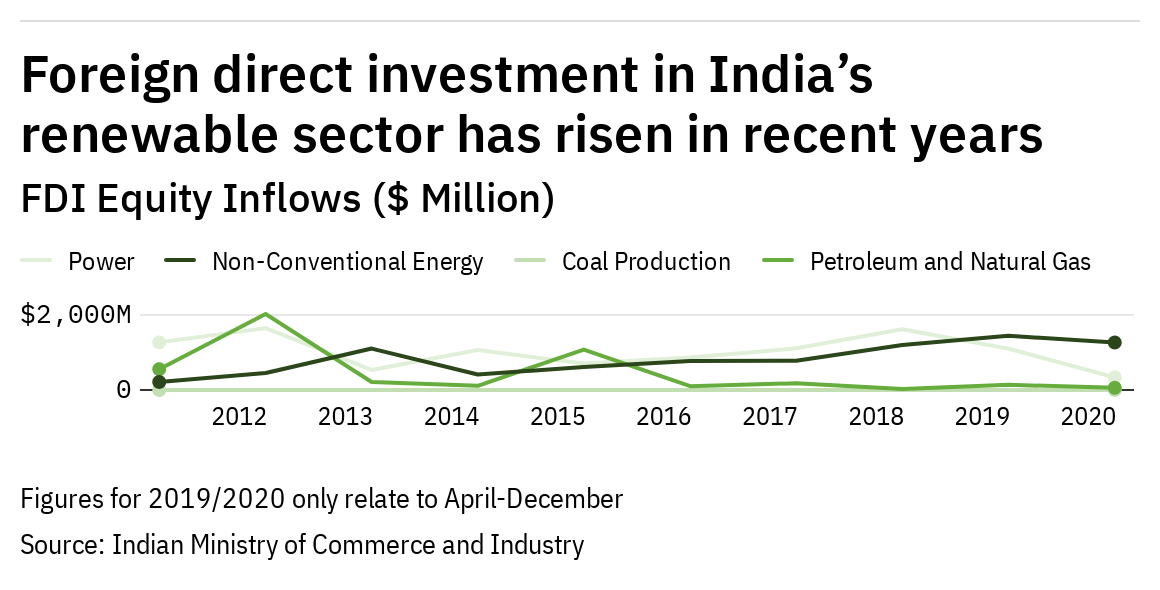

In contrast, the country has seen an influx of funds, from global pension sovereign funds and private equity investors, for investments in renewable energy. It is time to find some common ground for the government and investors that helps meet growth expectations and leads to long-term sustainable growth.

The NIP, along with the power sector reforms currently underway, including those in wholesale electricity markets, should drive investment in economically, and environmentally, efficient infrastructure.

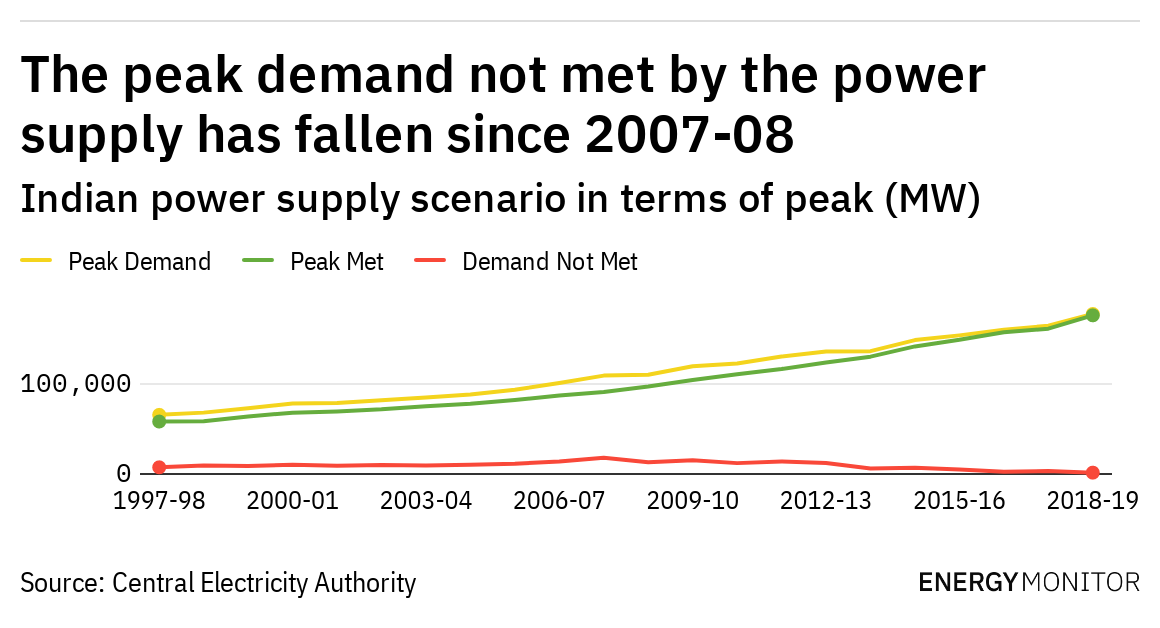

The 2003 Electricity Act delicensed the power generation business and led to a flurry of public and private investments in new power generation assets. New assets were considered vital given the increase in energy peaks and unmet demand, and the growth in GDP over the past ten years. As a result, around 124GW of new coal power plants were installed from 2010 to 2016, equal to about 62% of the country’s current coal capacity.

However, that investment story has resulted in a not-so-happy ending for many investors.

The capacity additions, which were meant to support the country’s export-oriented manufacturing-driven economic growth plans, suffered from demand failing to pick up as expected. As a result, several thermal plants are operating at historically low load factors. Many are struggling to meet their debt service requirements, let alone expectations of equity returns.

The all-India thermal power plant load factor has fallen from 77.5% in 2010 to 55.9% in 2020. Coal-fired power plants owned by NTPC, the country’s largest thermal power generating company, operated at load factors of 68.2% in 2020, down from the high of 80.2% in 2015.

Say’s law, which claims ‘supply creates its own demand’ or, more simply, ‘if you build it, they will come’, did not hold true for investors who developed gigawatts of thermal power plant capacity.

Government mega-schemes

The announcement of a five-year infrastructure investment plan in late 2019 was one of several central government-led mega-schemes aimed at providing long-term project pipeline visibility. Large-scale, multi-year construction infrastructure projects that can attract huge volumes of international and domestic capital at affordable costs are considered a priority to boost GDP. Such projects contribute significantly to direct and indirect job creation. Further, increased access to better infrastructure can lead to capital savings for businesses and increased labour productivity.

But not all infrastructure projects result in equal societal net benefits. Clean energy infrastructure investments not only add jobs and spur business activity, but also lead to greater benefits, such as carbon and other pollutant reductions plus public health improvements. A new thermal power plant will not create these external benefits.

And then there are the costs and economic benefits. The NIP focuses primarily on roads, urban housing, railway freight corridors and energy. The electricity sector allotment – 24% of the NIP budget – aims to stimulate the addition of 75GW of coal power stations and 100GW of renewable projects.

Given the low load factors of existing coal power plants, it does not make economic sense to further invest in creating assets that may remain mostly idle. Instead, infrastructure investment should focus on the renewable projects needed to meet energy demands arising from projected future economic growth. They would also help India to fast-track its transition to a cleaner growth economy and stimulate a post-Covid recovery. Adding more coal capacity will simply create greater environmental challenges for the future.

The NIP sets a target of an additional 100GW of renewable energy projects by 2025. This aim fits well with national renewable energy targets of 175GW by 2022 and 450GW by 2030. But the NIP’s signal for another 75GW of coal power plants is neither in tune with the reality of existing projects nor in line with the overarching theme of ‘One Sun, One World, One Grid’, Modi’s ambitious plan to transfer solar power to 140 countries through a common grid, of which India is a signatory.

Infrastructure is the missing piece in India’s economic growth story. However, the focus and prioritisation should be on building infrastructure that is required and desirable from a net societal benefits perspective. It is not advisable to fall into the trap of creating capital investments that are financially risky or of investing in projects that will quickly turn into non-performing assets, stressing banks and choking capital for deserving businesses and citizens.

“Build back better” should be a catchphrase, but it works if incorporated in plans and forecasts for future growth. There is no trade-off between green growth and economic recovery. In this context, the need for yet another round of investments in coal plants, when the existing ones are already under stress, needs serious discussion.

A version of this article originally appeared in Energy Monitor.